In Northern Ethiopia, the severe El Niño induced drought affected millions. But even in this vulnerable context, a quick humanitarian response linking relief, rehabilitation and development can sow the seeds for long-term resilience.

Fostering community resilience

What are resilient food systems?

Resilience has been embraced as an overarching theme by both the international humanitarian and development communities in recent years. It is based on the recognition that people are part of larger systems such as ecosystems, markets, and social networks that are constantly in flux with feedback loops between them. Resilience is understood as the ability of individuals, communities or systems to

- cope with and absorb the impacts of shocks (events) and trends (stresses) without sustaining permanent harm or damage (absorptive capacity),

- adjust and adapt to trends and events while still functioning in broadly the same way (adaptive capacity), and

- fundamentally when its current modus operandi are no longer viable (transformative capacity).

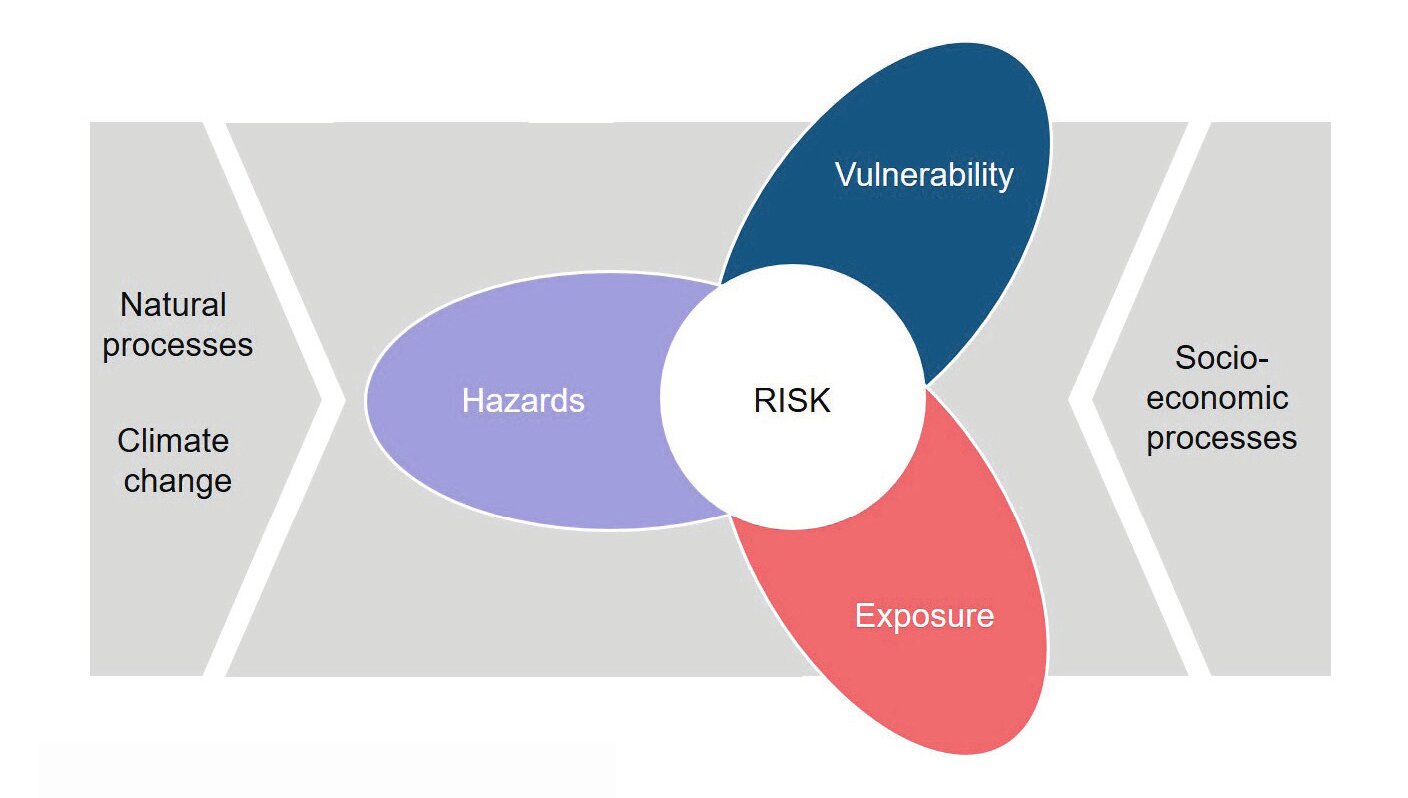

Resilience is thus the ability to deal with risks. Risks are the outcome of three factors: the hazard, the exposure to it and the nature and degree of vulnerability (Figure 1). Uncertain rainfall for example is a hazard to which rainfed farmers are particularly exposed. Families who only engage in rainfed farming, with no diversified income source, are most vulnerable to the hazard.

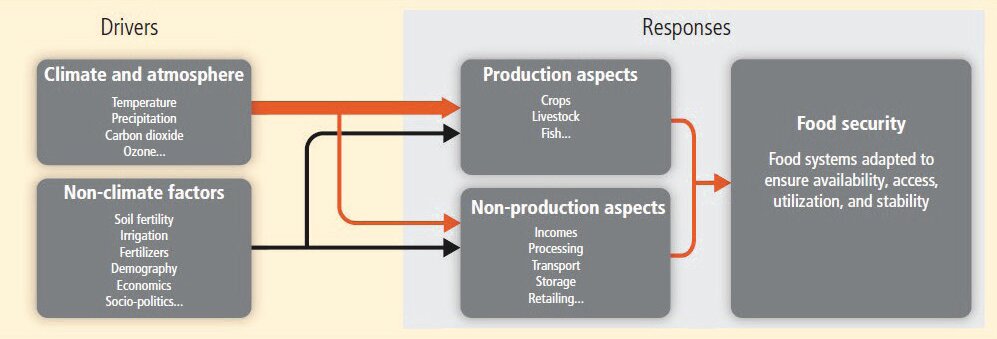

Food and nutrition security is the outcome of several processes related to production, processing, distribution, preparation and consumption of food that are in turn influenced by factors such as environment, people, inputs, processes, infrastructures and institutions. Resilient food systems would be those that have the ability to provide sufficient, accessible and nutritious food to all today and in the future in spite of various, unforeseen disturbances and trends. Figure 2 below shows the climate and non-climate related drivers of change that food systems face and the possible areas of response.

Resilience of food systems in the context of food crisis and recovery

Over the past years, the concept of resilience has greatly contributed to breaking the silos between humanitarian and development actions and to foster policies that address the complex causes of vulnerabilities and food crisis by a systemic, multi-sector approach and joint programming. Although the need for integrated and flexible programming is recognized, implementation often fails due to the de-facto persisting procedural and administrative barriers in donor and implementing agencies. It is also broadly agreed that a long-term investment in resilience-building “across the silos” greatly increases the cost-effectiveness of interventions related to recurrent crisis, since they reduce the financial, administrative and resource burdens of responses.

Responses to food crises and famine are beginning to incorporate resilience-building measures and long-term development efforts into relief actions. Many NGOs and UN agencies’ programmes today combine provision of food or cash for work on the rehabilitation of assets and infrastructures such as restoration of degraded land, reforestation or the rebuilding of wells. Such approaches have the potential to meaningfully contribute to resilience building of local communities during food crisis, but only if they are based on 1) thorough analysis of vulnerabilities before a shock, 2) consideration of disaster risk reduction aspects, and 3) ownership and institutional capacities of local and national governments to programme and support such action and to embed it into wider development plans. The current practice however shows that in many emergencies, most recovery activities are programmed short notice and rather detached from integrated development plans.

Building food system resilience in Wag-Himera, Ethiopia

With the objective to overcome the chronic food insecurity and repeated relief aid in the area, Helvetas launched the Wag-Himera Rural Future Initiative project in 2013, founded on a strong partnership with the local government of Wag-Himera zone and community based institutions. This project was followed by a contiguum of other projects, all aiming to strengthen the capacity of local administrations, extension services, community based organizations and the private sector in order to foster long-term strategies for resilience building. Key intervention strategies of the projects are 1) rehabilitation of severely degraded watersheds, 2) enhancing food security and agricultural productivity through improved farming and household asset building and 3) development of improved rural urban linkages and the establishment of value chains.

Helvetas’ experience in the zone shows that linking relief, rehabilitation and development (LRRD) enables multiple projects, working at different stages of the disaster cycle, to reinforce and complement their actions contributing to the resilience. The key entry point for enhancing food system resilience in Wag-Himera is sustainable natural resources management combined with locally adapted improved agriculture solutions:

- Intensive hillside farming through bench terraces: Since 2013, bench terraces were successfully initiated and promoted as an effective soil and water conservation measure to repair and control the damaging impacts of ploughing in extremely steep slopes of Wag-Himera.

- Moisture conservation tillage: Helvetas promoted contour ploughing, broad furrowing, tied ridging and the use of moisture conservation tilling devices to reduce rainwater runoff and erosion and to increase water infiltration. Compared to conventional tilling, the new practice enhanced farmer’s yields by 33 to 47 percent.

- Promotion of controlled grazing and fodder production: The project promoted controlled grazing, cut and carry practices, the provision of supportive grazing tools such as peg and rope for livestock tethering and the planting of multi-purpose tree seedlings to boost fodder sources. Through this, a total of 6,650 ha of land were preserved.

- Roof water-harvesting system: In the absence of safe ground-water or springs, Helvetas has developed the Kalamino Cistern (Image 1) as an innovative solution to overcome the severe drinking-water constraints.

- Effective homestead gardens: Through in-situ water harvesting such as ring basin infiltration pits (Slider) and ponds collection of run-off rainwater (Image 2) is promoted, allowing families to do perma-gardening, and vegetable and fruit production. The horticulture produce generates additional income and enriches the diets of the families.

- Promotion of diversified livelihood options: A set of high value, nutritious and drought tolerant crops were introduced to households. In addition, backyard poultry and beekeeping were strengthened – all valuable contributions to the families’ nutrition as well as a source of income to purchase supplementary food during periods of shortage. During the 2015/16 drought, as a part of recovery measures, Helvetas promoted the Madagascar bean, a drought resistant, nutrient rich and high yielding crop.

- Humanitarian relief to absorb 2015/16 shock: In order to meet the immediate needs of communities in Wag-Himera during the drought, Helvetas launched a short-term humanitarian response project, providing families with drinking water, livestock feed and seed. The intervention helped sustain the absorptive capacities of the families.

- Social and economic empowerment of women: Across all projects, Helvetas put an emphasis on the access of women to resilience building capacities and assets. The projects foster access of women to extension services for improved agronomic practices, effective low cost technologies and alternative options for income generation.

What did we learn?

Through soil and moisture conservation measures and drought tolerant varieties the projects enhanced the capacity of the communities to produce diverse foods locally and sustain production, to increase productivity and reduce harvest losses during dry spells. Measures against soil erosion combined with controlled grazing and fodder production helped in preserving and restoring soils, biodiversity and water resources – a precondition for resilience. In-situ water harvesting, perma-gardening, poultry and beekeeping contributed to a more diverse food basket and thus a better nutritional base for the families. At the same time, they created additional income sources that help bridging lean seasons and mitigating future food crisis. The better access to safe drinking water from roof water harvesting and cistern systems reduces the risks of waterborne diseases, thus enhancing the nutritional uptake of the food consumed by children, women and men. Overall, more than 17’000 households have improved their access to food, hence reaching a total of roughly 100’000 people which is nearly 20 percent of the population living in the zone. Most importantly however, the projects successfully engaged the entire zone’s administrative establishment, extension services, the civil society and local small enterprises to invest in resilience building. The adoption and replication of the knowhow, technologies and methodologies developed by these actors is the most essential guarantee that food system and climate change resilience building will continue to be pursued in the future.

At the same time, different challenges lie ahead. Given its multi-dimensional nature, measuring resilience is complex. So far, there are no widely accepted tools to measure resilience comprehensively. For food system resilience, measuring nutrition outcomes and their interlinkage with agriculture, water and sanitation will need more thorough attention in future. Furthermore, seeing the trend towards a dryer climate with erratic rainfalls and extreme weather events forecasted for Northern Ethiopia, the transformative capacities of communities in Wag-Himera and neighbouring zones should become a priority in the coming years. Not only do farmer communities need the capacity to further adapt their agricultural practices to a dryer climate, they also need alternatives for livelihoods that are less dependent on farming to generate income and ensure food security.