The technical and vocational education and training (TVET) sector in Uzbekistan has weathered dramatic changes in recent years, creating challenges not only for the people delivering and participating in TVET, but also those charged with leading the sector.

At the end of 2022, a Helvetas-commissioned study by the CEMETS Education Systems Reform Lab, which is part of the public research university ETH Zurich, highlighted some of the challenges involved with governing TVET in Uzbekistan. New changes implemented at the start of 2023 have already altered the TVET landscape, but the fundamental challenges remain the same.

Navigating a changing context

Until the end of the last decade, TVET was the main education pathway for young people in Uzbekistan. In 2015, 93% percent of all students in upper secondary education were in TVET (ETF 2017). Through 2017, TVET was part of the country’s 11-year compulsory education. The education sector reform, which was formalized in 2019, replaced compulsory TVET education with optional, fee-based TVET programs that last 1.5 to 2 years.

Nearly 1,500 TVET institutions had been delivering training to over a million students before 2017 according to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), but the sector has largely collapsed since the reform. Today, UNESCO reports that only 23.2% of Uzbekistan’s youth participate in TVET. This is low compared to an average just over 40% in OECD countries or over 60% in Switzerland (OECD), and probably too few to meet employers’ needs for skills.

The TVET sector had governance challenges when it was part of the compulsory education system, and those challenges were exacerbated by the change. According to the ADB, skills mismatch was a major problem. Employers could not find the skills they needed to grow, especially industrial enterprises among whom nearly half could not find the qualified workers they needed. This was driven by the system’s focus on knowledge rather than competencies, the lack of workplace learning, and issues with processes of assessment, certification and curriculum development. There was little career guidance for students and very limited interfacing between TVET and industry. In general, TVET was unable to connect skills supply and demand.

Until 2022, 13 ministries and 14 agencies were charged with aspects of coordinating skills development and delivering TVET. At the start of 2023, the latest presidential decree merged a number of ministries: the government was reduced from 25 to 21 ministries and from 61 to 28 agencies. As a result, about 20 ministries and agencies (instead of the previous 27) are now responsible for TVET. This leads to fewer “owners” of TVET and more focused mandates, but fragmentation remains an issue. The advantage of this reform is that public structures are being reduced , the system is more coherent and with prospects to function better in terms of coordination and clarity of mandates. These changes have been extensively advocated for by Helvetas Uzbekistan within the frameworks of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation-funded VET4UZ project, a systemic intervention designed to support TVET reform in Uzbekistan by improving governance, building quality assurance practices, and increasing teacher performance and private sector engagement.

As part of these reforms, the Ministry of Higher Education and TVET became the Ministry of Higher Education, Science, and Innovation. The function of Deputy Minister for TVET was eliminated, effectively cutting the TVET sector out of the highest levels of governance and making its leadership unclear, for instance the VET colleges have two “parents”: the Ministry of Higher Education and TVET, and the line ministry, their roles and responsibilities being often blurred. Despite these changes, most ministries remain involved in TVET governance, including ministries like Tourism, Agriculture, and Labor. These ministries do not have any authority over curriculum content, but do receive and direct funding for the TVET colleges under their authority.

The effects of fragmented TVET governance

In 2022, Helvetas Uzbekistan partnered with ETH Zurich to produce a study of TVET governance in Uzbekistan based on 646 survey responses across all levels and actors involved in TVET governance. The study found that satisfaction with TVET governance is low—approximately 2.2 on a 1-to-5-point scale—both in general and for every aspect of governance. Actors at the national level are somewhat more satisfied than lower-level actors by about half a point.

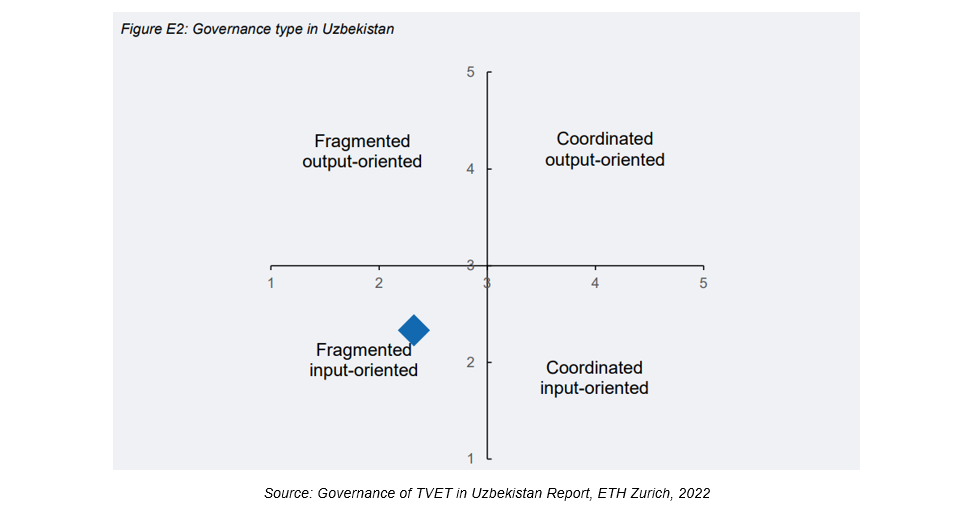

The study found that TVET governance in Uzbekistan is fragmented, as opposed to coordinated, and oriented towards governance of inputs rather than outputs. This input-oriented governance means that the government is focused on providing TVET schools with direct inputs like learning materials, infrastructure, and teacher salaries. An output-oriented strategy involves providing funding per student (“money follows the student” approach) and allowing providers to self-manage as long as standards are met. Fragmentation and input orientation are not necessarily problems, but the low satisfaction with this governance style and other indicators indicate that the approach is not working well for Uzbekistan.

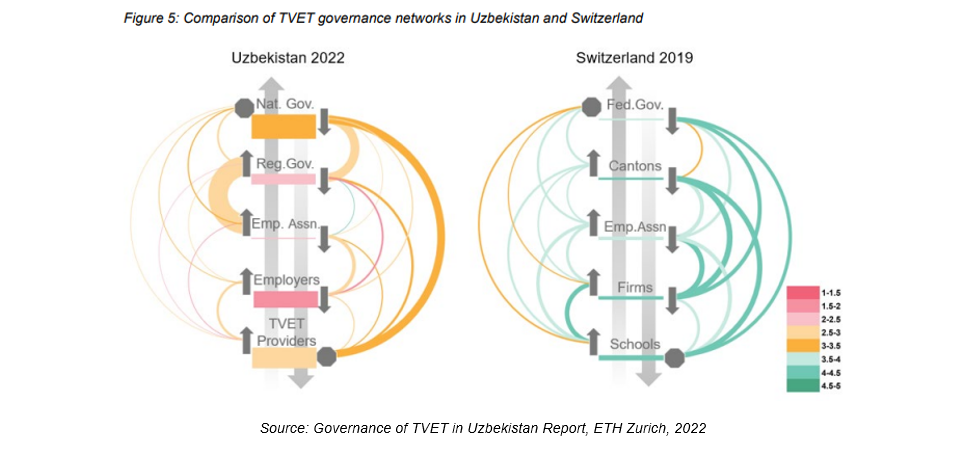

Finally, the study looked at how actors interact for TVET governance. Ideally, TVET governance is a network with employers and employer associations playing important roles alongside ministries, regional line ministries, and TVET providers. The previous study done by ETH Zurich and Helvetas Uzbekistan in 2021 found that education-employment linkage is very low in the Uzbek TVET sector, and the governance results showed why. While employer associations are typically key intermediaries, Uzbek associations are in their infancy and are outsiders in the governance network for TVET. They have weak relations to employers themselves, and no employer reported a relation to an association. As a consequence, employers are bombarded by requests from other actors and from each other and linkage remains low while all actors in the network find cooperation arduous and unsatisfying.

Shifting focus to outputs and outcomes

The 2022 study concludes with four recommendations:

- Shift from input-oriented governance toward output-oriented governance.

- Prioritize a cooperative governance network in which employer associations are true intermediaries facilitating employer leadership of TVET.

- Focus on improving career guidance and counseling, system permeability i.e. navigating between different career pathways vertically and horizontally), and clear financing and incentives to improve TVET governance performance.

- Focus on solving fundamental system problems, treating quality as an outcome rather than an input.

Although the study highlights the issue of fragmentation, it does not prioritize that problem in its recommendations. The recommendations instead focus on moving towards output-oriented governance, prioritizing cooperation—especially with employers and associations, improving career guidance, and treating quality as an outcome of solving critical problems rather than a goal in itself.

The 2023 reforms are intended to combat fragmentation across government, but TVET remains fragmented across ministries. Instead of clearer leadership, TVET providers and employers are left without representation at the highest levels of governance and facing the same complex funding and regulation situation they had before. Although fragmentation was an issue, input-oriented governance was the more pressing issue before the reform. If anything, the reform makes this situation more urgent. TVET providers lack the freedom to manage their institutions and have incentives to maximize spending on infrastructure and equipment without considering effectiveness. An output-oriented system would focus on students’ attainment of standards. This would help stabilize the TVET sector for providers while allowing for innovation, work-based learning, and other much-needed changes.

About the Author

Dr. Gabriela Damian-Timoshenco is the Team Leader for the VET4UZ project. She has almost 20 years of experience in project design and implementation in skills development and labor market support, and has worked to adapt VET concepts and ideas to local contexts in 13 countries.