Applying systems thinking is the nesting doll of development. Remember those wooden dolls that tourists buy as a souvenir when visiting one of the Eastern European countries? The nesting dolls are a set of beautifully painted wooden dolls of decreasing size placed one inside another.

So the development nesting doll goes like this: If you want to help a poor man, don’t just give him a fish; teach him how to fish. Open the next doll: Don’t just teach a poor man how to fish; train the trainers to teach more poor women and men how to fish. And we go further: Don’t just train the trainers; change the curriculum of training institutions that train future fishing instructors. And then further: Build links between educational institutions and the fishing industry to develop and deliver more market-oriented vocational training … and so on. You get it.

The point is that as you move from the outer to the inner layers of the development doll your chances of achieving more sustainable and large-scale impact increase. Rather than addressing only symptoms (giving a poor man a fish) you open the next doll to identify and address systemic root causes of the problem at hand. This has become widely accepted knowledge as many organizations, including Helvetas, started to apply systems thinking.

The number of dolls opened also defines the difference between humanitarian aid and development cooperation. An emergency requires rapid action for immediate relief—there’s no time to open many dolls—while development cooperation is designed to address systemic failures to achieve long-term impact. This requires deeper understanding of causal relationships. Often these two worlds collide, and the focus gravitates around the middle doll. At Helvetas we call this the nexus: linking emergency response with longer-term initiatives, as we do now in Ukraine.

All of this is common knowledge among development practitioners. So I’ll skip an explanation on what applied systems thinking is, why it is important, and that its principles and frameworks are widely applicable to different thematic areas, including green transition. There are established resource libraries that do this well (e.g., BEAM Exchange and Marketlinks) and in-depth articles that unpack the systemic approach. Below I’d like to reflect on a topic that’s been weighing on my mind for some time, in large part because it greatly affects the future of my work.

Localization is at the heart of systems thinking

The decolonization debate is raging in the development community, exacerbated by a shift towards populist politics and public discourse in the traditional donor countries, including Switzerland, the home of Helvetas. The role of INGOs is put into question, with them often portrayed as the middlemen siphoning off public funds intended for the poor and vulnerable. Some donors are reverting to direct support of local institutions and actors under the pretext of strengthening “localization” of development.

So what role is there still to play for Helvetas and other INGOs?

I start feeling my 20 years of work in development when I say: “This debate is not new.” In fact, localization lies at the heart of applied systems thinking. And it’s a healthy debate—one that we need to continuously have in our work as development practitioners.

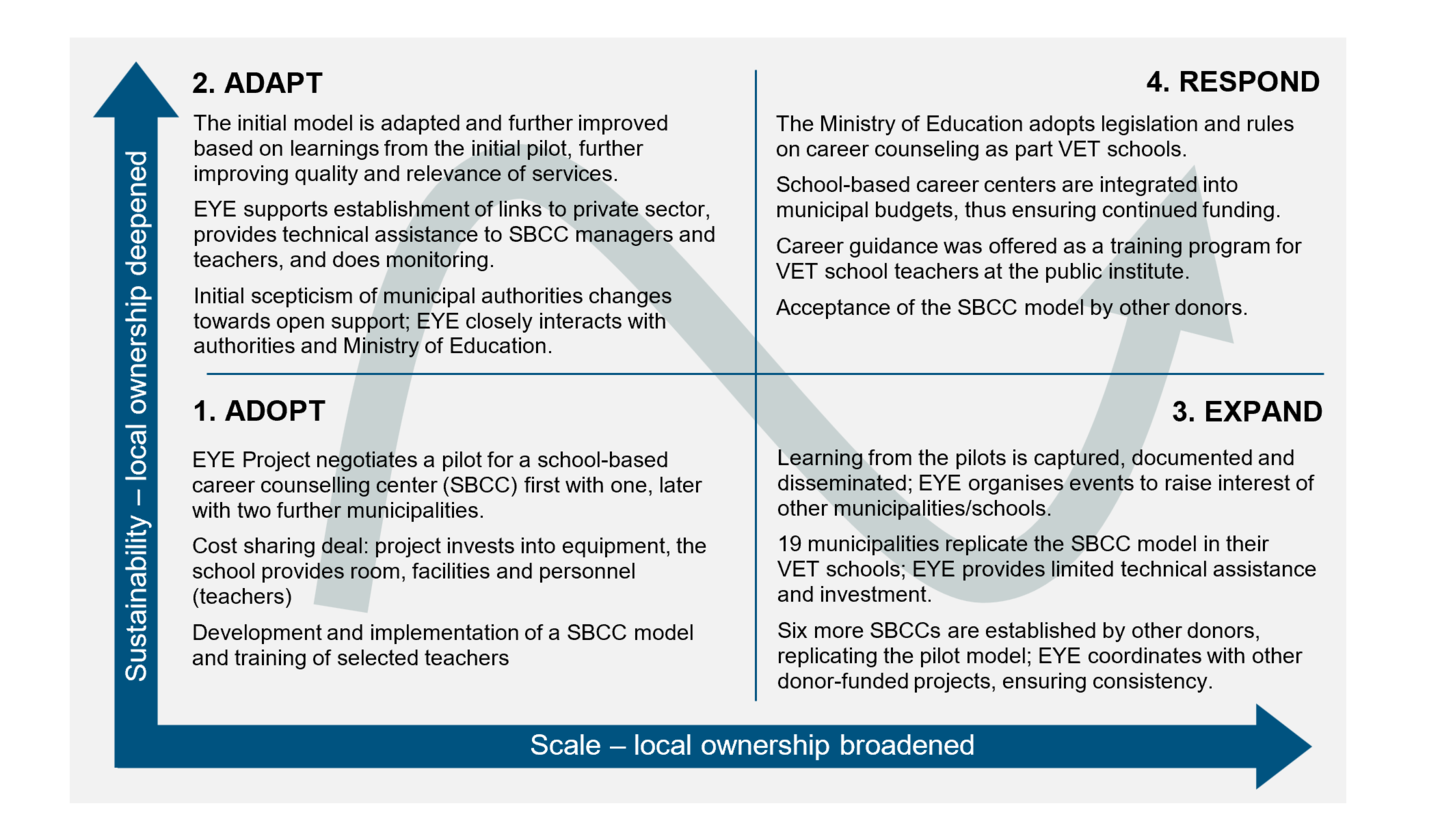

When I speak to my colleagues about their project activities and partnerships formed around these, one of my favorite tools I always have in mind is the adopt-adapt-expand-respond matrix (referred to as the AAER framework and covered in depth in this guide). It’s all about localization—building meaningful partnerships and deepening and widening local ownership over change processes that lead to more resilient systems.

Helvetas recently closed a project in Kosovo that we were implementing for the Swiss Embassy there: the Enhancing Youth Employment (EYE) project. Over the last year we invested significant efforts in documenting and sharing lessons learned over the 12 years of implementation. One of the successful initiatives (there were also unsuccessful ones) focused on establishing school-based career counseling (SBCC) centers across the country.

The problem that needed to be resolved was that too many young people in Kosovo were channeled into less productive or oversaturated job markets due to the absence of appropriate career counseling when choosing their professions or applying for jobs. As a result, many skilled youth ended up being unemployed, leading to increased migration pressure and social fragility. But then EYE intervened with a model shown in detail in the graph below.

The outcomes of the systemic changes in school-based career counselling are the result of true local ownership and commitment. Since the initiative started in 2016, more than 150,000 career counselling sessions have been provided to students, thanks to which 1,600 could also be matched with job vacancies. For a small country like Kosovo, with only 1.6 million inhabitants, this is a large number; scale is always relative to the absorption capacity of local systems. And the number of students benefitting from improved career counselling grows further as the 25 established career centers continue to function with the financial backing of municipalities, who clearly understand the benefits these centers have for their young constituents.

Of course, the reality is messier, characterized by collaboration with multiple actors, learning through trial and error, and continuous adaptation to achieve the best outcomes (much in line with USAID’s CLA approach). A strategy for localization requires investment into partnerships and readiness to engage on a path that is complex and long, with the AAER framework helping us to synthesize and understand what is essential.

The EYE team documented its learnings about partnerships as the foundation of systemic development cooperation here. I have worked with the EYE team from the start of the project in 2012 and have been involved in other systems change projects over the years. In this time I have seen many examples of what works—and what doesn’t. In addition to the EYE team’s findings, these are some of my personal learnings around the essential building blocks for effective system change partnerships:

- Successful development cooperation starts with a good understanding of the capacities and incentives of local actors. Here the MSD guide offers a great assessment tool that helps to define the entry point for partnerships: Is my entry point focused on capacity building and knowledge transfer, or is it about changing incentive structures that impede local actors to act in a way that produces better outcomes (e.g., in terms of social inclusion or environmental sustainability)? Based on this, an agreement is made that is relevant and truly complementary to what the partner can co-invest. It is the basis for establishing an eye-to-eye partnership with local actors.

- This type of partnership requires responsiveness: Helvetas never enters an engagement with a ready-made solution and plan. Our starting point is a dialogue with our partners, whereby we jointly assess the problems at hand, develop ideas and solutions together, and embark on a joint learning path. Adaptive management is part of applied systems thinking, supported by an effective system for monitoring, evaluation and learning (in Helvetas we use the DCED Standard, which works well for this purpose). The partners of EYE appreciated the readiness of the project team to respond to their needs and changing circumstances—and it put them in the driving seat.

- Often we get over-invested in partnerships at a pilot stage. The example of EYE shows the importance of letting go at some point in time and investing in the nurturing of followers—we call that crowding-in. I have seen numerous development initiatives fail because they did too little too late to move from pilot to scale or they assumed that crowding-in would happen automatically (“If they see the benefit, they’ll follow”). Over-investment into individual partnerships also raises the entry bar for others since they do not have access to a similar level of support. The EYE example shows that crowding-in requires active and distinctive project partnerships with different system actors who perform different roles in the SBCC system, such as the public institution for teachers training or the Ministry of Education for setting the legal and regulatory framework.

- It is therefore important to develop a shared vision of system change together with our local partners at an early stage. Too often we are focused on those local actors that can provide solutions to the problem at hand (e.g., career counseling of youth by VET Schools). However, to achieve sustainability we need to understand what it takes for these actors to maintain their new role in a system. SBCC in Kosovo can continue to function only if municipalities provide funding, if teachers are trained in counseling, if linkages are established with the private sector, and if information about labor market trends and job vacancies is continuously updated. This is why systems thinking is so important: It helps us to understand who all plays important roles in a system. It also helps to both deepen and broaden the extent of local ownership over system change as projects engage with multiple actors.

- In implementing projects like EYE, we understood the importance of building and maintaining partnerships for system change. This is a hugely complex task for project teams and requires specialized skills to do it effectively. This is why we need to invest in capacity building and coaching for INGO staff. In Helvetas’ trainings on applied systems thinking, we introduce various tools that are useful to assess the roles and relationships of local actors (e.g., the AAER framework or the Political Economy and Power Analysis tool), identify relevant partners, and develop a meaningful and reciprocal relationship with them. We conduct regular reviews based on our MEL system to assess progress and challenge underlying assumptions of partnerships.

In her recently published book “The INGO Problem,” Deborah Doane emphasizes the need for INGOs to shift towards a facilitative role and embrace the principles of subsidiarity—operating as locally as possible and as internationally as necessary—and solidarity, fostering equitable partnerships with local organizations. The EYE project’s learnings add to this evidence base, demonstrating the continued value-added role of an INGO like Helvetas. This role needs to be embedded into applied systems thinking that emphasizes the reciprocal nature of partnerships and localization, measuring success by the extent to which local actors initiate and own systemic change.

Uncovering deeper levels of complexity

In revisiting the metaphor of the development nesting doll, we see how its nested complexity mirrors the layered nature of systemic change. From providing immediate relief to embedding long-term, sustainable transformation, the doll serves as a reminder of the need to unpack deeper layers of systems thinking to achieve meaningful impact. The EYE project in Kosovo exemplifies this progression, demonstrating how each "doll"—from partnerships with VET schools during pilots to partnerships with other actors that perform complementary roles in the SBCC system—contributes to a cohesive strategy for fostering local ownership and resilience.

At the heart of this approach is a commitment to collaboration and adaptability. Effective systemic change requires not only the identification of root causes but also the empowerment of local actors to own and sustain solutions. By aligning our roles as INGOs with the principles of subsidiarity and solidarity, as Doane emphasizes, we position ourselves as facilitators of locally driven transformation rather than as external intermediaries.

Ultimately, systems thinking challenges us to think beyond individual projects and to consider the broader, interconnected systems in which they operate. Like the nesting dolls, success lies in uncovering deeper levels of complexity and ensuring that each layer contributes to a resilient and inclusive whole. This requires persistence, reflection and a readiness to let go when local actors are equipped to carry the torch forward—a lesson we must carry into all facets of development cooperation.