Spices have enriched human diets for centuries. Numerous books have been written about ancient spice trades, wars fought over them, fortunes made and lost. Yet as we survey rows of neatly arranged spice jars on supermarket shelves, how much do we think about the people behind them – especially the producers, many of whom are small farmers in low-income countries? This is the first in a series of blogs about how international cooperation efforts can improve the lives of some of those farmers and their natural environment. But first, a few facts that might – or might not – surprise you.

1. Sourced from several different tree species

Cinnamon comes from the bark of a tree – or rather, the bark of a number of different trees all belonging to the genus Cinnamonum. Two are important commercially; “true” or Sri Lankan cinnamon, C. verrum, which is known for its mild, sweet flavor and soft bark, and so-called Chinese cinnamon, C. cassia, which has a spicier flavor and harder bark. The sticks of flaky, rolled bark that are a common Christmas decoration and flavoring for mulled wines and punches are Sri Lankan cinnamon. Which type of cinnamon we buy in powdered form may be less obvious unless there is a clear indication of origin.

“True” cinnamon, as its trade name suggests, originates from Sri Lanka, although it is also grown in India (the Hindi name for cinnamon, dalchini, means “sweet bark”). “Chinese” cinnamon occurs naturally in forests of southern China and northern Vietnam, and is widely cultivated, sometimes in dense plantations.

2. An essential ingredient in Chinese medicine

The world market for cinnamon is heavily influenced by China – where the demand for it is driven by its use in traditional medicine. The compound in cinnamon that is important in this case is cinnamaldehyde, which occurs in highest levels in Cinnamonum cassia. Figures on the volume of world trade in cinnamon vary according to source and fluctuate somewhat; one source (Mordor intelligence) estimates the current global market to be worth USD 1.57 billion, with strong predicted growth in future.

3. A wealth generator for ethnic minorities in Vietnam

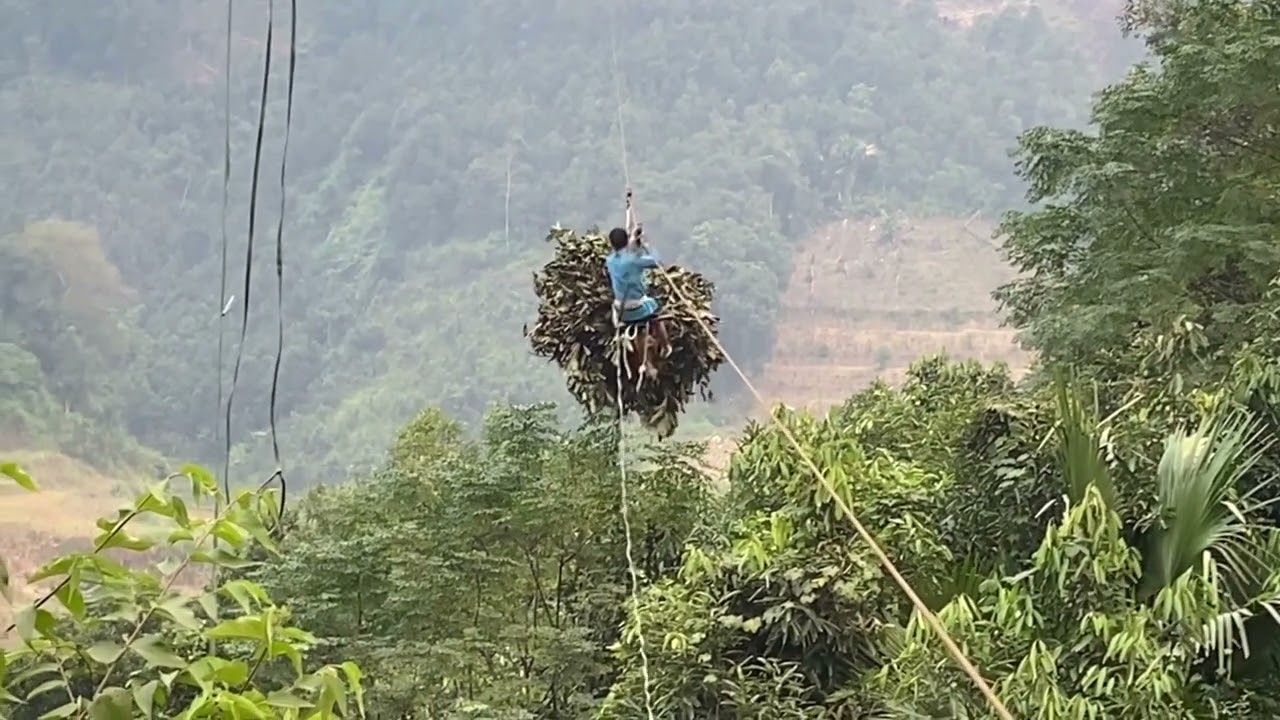

In the past 20-30 years, many ethnic minority households in Vietnam have seen their lives transformed through cinnamon. In provinces such as Yen Bai and Lao Cai, cinnamon trees are cultivated in dense plantations that cover the landscape as far as the eye can see. Every part of the tree is used. Once felled, the tree is stripped of its bark, which is sorted according to size and thickness. The leaves are removed to extract their essential oil through distillation. Small woody branches are burned for fuel, whilst the timber is used in construction. In this way the tree is multipurpose and almost unmatched in terms of its economic value. Many poor households that farm cinnamon have experienced a transition from real hunger and poverty to relative comfort in a single generation. Furthermore, many now benefit from premium prices paid for organic production.

“I was born in 1974, and when I was small, we knew real hunger. Many people did. We grew paddy and some upland rice, but it wasn’t enough,” said Triệu A Sơn, a cinnamon farmer from the Dao ethnic group that lives in Lào Cai province. “Cinnamon has changed our lives. We started growing it in the 1990s, and now there are cinnamon plantations everywhere. There is no more hunger, and we have nice houses and a road connecting us to the market. Most of us have motorbikes; within the village there are even 20 cars.”

Triệu A Sơn, a cinnamon farmer from Lào Cai province

4. A loss of biodiversity

The increase in living standards gained by the Vietnamese cinnamon farmers is of course a huge achievement, especially since ethnic minorities have often been the last to benefit from development interventions. Yet as the same farmer, Triệu A Sơn, admitted, the natural forest surrounding his village has gone – and with it, the birds, animals and a whole range of different plants. Not all of this can be blamed on cinnamon cultivation. Reforestation or afforestation with economically attractive tree species can be traced back to the 1980s, when the government of Vietnam sought to halt the clearance of forest for subsistence agriculture in upland areas. Each local household had the opportunity to take responsibility for tree planting on a plot; cinnamon turned out to be the most rewarding species, in many cases. Arguably, a dense cover of cinnamon trees is still better than the soil erosion caused by slash and burn cultivation on steep slopes.

Nevertheless, heavy dependence on a single crop is never wise. Prices could drop. Pests could spread rapidly through the dense plantations. In the context of rising temperatures and uncertain rainfall patterns due to climate change, there is also a risk of new diseases and forest fires.

5. The role of Helvetas

Since 2016, Helvetas has been implementing a Regional Biotrade Project on behalf of the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO). The project seeks to promote an export market in “bio-friendly” products from Vietnam, Laos and Myanmar. When the project began, the export market for the selected products was almost entirely oriented to China or other countries in the region, where organic certification is rarely required. In the first phase, the focus was therefore on promoting a market for products with organic certification, largely destined for Europe or North America. The demand for organically certified cinnamon has jumped accordingly, putting more money into the hands of producers and processors along the value chain.

In the second phase, the project is seeking to go beyond organic – towards promoting production that supports the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, as advocated in UNCTAD’s BioTrade Principles. In the provinces of Yen Bai and Lao Cai, this is a very challenging task. Here the project is working with the Union for Ethical Biotrade, UEBT, in establishing Biodiversity Action Plans and model farms that have a greater cropping diversity (learn more about this initiative here).

Where there is greater hope for biodiversity-friendly production is in the far northeast of the country in Cao Bang province. In this area of karst hills rising abruptly out of flat paddy lands, the landscape is more diverse, and the forest, too – with cinnamon forming one of a mixture of cultivated species. It is even, it seems, a different species of cinnamon – but that is another story. More can be found about it here.

Thanks to Jos Van der Zanden, Team Leader and Dieu Chi Nguyen, Deputy Team Leader, Regional Biotrade Project II, for their helpful inputs to the text.