A healthy dosage of skepticism is helpful. It sometimes aids in the separation of fact from fiction. Yet, skepticism becomes a dogma in the face of a constant stream of evidence demonstrating environmental degradation and climate change. This is not a conviction. It is a conclusion. Numerous studies corroborate this. So, for us, no time to lament about the doubts and lack of action.

You may wonder why. The effects of climate change are worsening much faster than anticipated. Thus, every choice made, and every fund invested in the green economy and divested from fossil fuels matters. As a reminder, the recently Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report sets the "code red for humanity". It reiterates the urgency for a global transition toward a net-zero economy and investing in adaptation capacity.

Saleemul Huq is a renowned expert on climate change and development. In one of our recent conversations with Saleemul, he clearly stated that "the house [earth] is already on fire. It’s too late to be sad.” This calls for urgent action. The aim is not just to extinguish the fire; we should also address systemic constraints and accelerate green transition. Don’t you think?

Helvetas has joined to take concrete actions. In its newly adopted Strategy for 2021-2024, Helvetas recognizes the importance of taking action. The organization supports vulnerable groups to be better prepared for climate change, adapt to it, and mitigate its causes.

There are examples of how the organization’s strategy has been translated into actions. Here is one example, which is the focus of our blog.

Helvetas has partnered with the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida). The two organizations designed a regional initiative called RECONOMY to address inclusive and green economic development in 12 countries of the Eastern Partnership (EaP) and the Western Balkan regions.

The countries in the two regions have one of the highest levels of air pollution in Europe and related premature mortality rates. They also record the fastest-rising temperature and deadly natural hazards, and their outdated industrial and agricultural practices keep them behind needed decarbonization trends.

Our understanding of the trends of green transition

By green transition, we mean increased investment by public and private actors that reduce carbon emissions and pollution, enhance energy and resource efficiency, and prevent the loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services. Transformations only emerge with a revamped industrial revolution. This seeks better use of natural resources for a more equal and healthy society. In other words, transformation requires rethinking economic, environmental, and social policies and how they relate to each other.

Unfortunately, a transition that has to enter transformation has taken longer than expected. Part of the reason is that we did not take the necessary steps to change how we live, govern, consume, spend, and produce. What does that mean for all of us? Our analysis in RECONOMY of the EaP and the Western Balkan regions identified four key drivers of the green transition.

The first is the way of life and behavior. These are about modifying societal norms, regulations, and behavioral patterns to support the green transition. What is lacking in the two regions is both public access to decision-making and the necessary degree of awareness. Thus, they are unable to keep up with global trends. High unemployment and pervasive economic and financial "short-termism" are present in markets, governments, and corporations.

Nevertheless, environmental issues are gaining public attention in the regions. They are gradually becoming a source of shifting market demands as well as a conduit for democratization. The perception of the European Union as an export market for the EaP and the Western Balkan countries also acts as a motivating factor for businesses to cater to consumers’ needs.

Second, regulators and businesses worldwide are beginning to prioritize financial concerns associated with the environment and climate change. This indicates that countries and businesses frequently assess their adaptability to climate change, environmental degradation, and decarbonization transition risks and adjust their strategy.

That said, environmental requirements in the international value chains are also tightening and have become a clear trend affecting trade. Policies that influence enterprises and people in the EaP and the Western Balkan regions are increasingly introducing extended producer responsibility (EPR) and due diligence requirements for environment and social governance (ESG).

Third, the volume of green financing is increasing internationally and in the EaP and the Western Balkan regions. This is true despite the numerous financing barriers in the regions at all levels, particularly for women-owned and rural enterprises. The Sustainable Finance Directive and the European Union Taxonomy were adopted by the European Union. Although both regions are still growing, they are trying to keep up with regional and worldwide trends. For example, Georgia has recently adopted a national-level Taxonomy, while Armenia is in the process of developing it.

Fourth, well-orchestrated twinning of green and digital transition is a key instrument in the "building back better". Technologies can help vulnerable populations obtain better jobs and earn more (e.g., by creating new jobs in circular ecosystems or reducing the costs of food producers with precise agriculture). However, the two regions need improved access to new technologies, which should be supported by a favorable policy climate, access to finance, and raising market beneficiaries' understanding and skills.

Walking the talk...

The war in Ukraine has made the green transition an even greater strategic priority for sustainable development in the EaP and the Western Balkan regions. The actors there are increasingly feeling the urgency to adhere to the EU climate and environmental acquis, improve the business models, and look for green and inclusive innovations to sustain the growth potential. Regional value chain destruction and the critical need for diversification of the market opportunities have accelerated the demand for European integration.

We have made progress in RECONOMY’s design and implementation of the environment and climate change integration method that is appropriate for the regional context, the program's existing operating modalities, and the market systems development (MSD) approach. By launching the package of pilot interventions within the parameters of RECONOMY, the program was able to evaluate the environment and climate change mainstreaming procedures, spanning the early stages of pilots' design, the selection of the partners, and further collaborative fine-tuning of the interventions.

We’ve worked to strengthen the program’s ability to promote changes in the market systems of the regions that will lead to inclusive transition, net-zero development, and climate-resilient growth. In light of this, we have identified the main political, economic, and environmental transition facilitators and barriers in the EaP and the Western Balkan regions. We have incorporated the enablers and constraints into the planning of RECONOMY's initiatives to mitigate any potential harm to the environment and prevent climate change while also strengthening the partner organizations' capacities.

Partners are crucial in ensuring ownership and scale after the program ends. Thus, we have stressed the need for partner assessment. This includes the capacity of partners (e.g., green transition understanding) and their incentives (e.g., to invest and take risks). Our assessment has uncovered important topics of relevance about the partners' organizational capabilities, the backdrop of the green transition, and critical instruments.

We considered the potential and demands for introducing green transition and creating green jobs, enhancing labor skills, raising wages, and utilizing sustainability as a competitive advantage for businesses as relevant entry points to contribute to economic and environmental value additions.

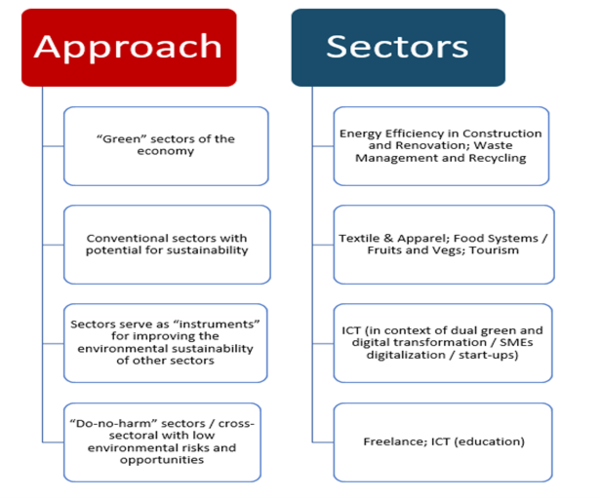

A few examples include the opportunity for the integration of circular economic models and eco-modernization of businesses, as well as the growing demand for sustainability from customers, clients, and investors. Another example is the application of innovative solutions as a result of the pairing of digitalization and green development. We used different sectors as entry points to support business models (e.g., energy efficiency in construction; circular economy in the textile and apparel industry), resilience and adaption (e.g., tourism and agribusiness), and do-no-harm (e.g., ICT).

We have also made headway in defining "green jobs" and "green skills," a difficult task that calls for a range of strategies. We used sectoral and skills-based techniques to define green skills and jobs. Employment in "green" industries is the focus of the sectoral strategy. Since it is presumed that every job in the selected industry is "green" in this situation, further effort in defining is not required.

When the goal is to promote environmental sustainability in traditional industries, a skills-based approach to assessing the additions to present or new jobs is more informative—even though it requires more work to examine the data. Combining these methods will also provide a foundation for defining the “green” indicators in the program, alongside lower-level and context-oriented indicators.

Our learnings

Environment and climate change, on the one hand, and inclusive economic development, on the other, are not competing objectives. We have fallen behind in developing our internal capabilities and those of our partners. The goal has been to establish shared knowledge and ideals to implement and realize the transition to a green economy (e.g., through mainstreaming green economic opportunities and specifically targeting the opportunities in the development of interventions).

Partner organizations often lacked capabilities and understanding (including integration of environment and climate change aspects in their strategies and operations). Finding the gaps and filling them has begun.

Our efforts are addressing both adaptation and mitigation. We have focused on enhancing awareness, co-creating business models, and supporting private sector-led advocacy for an improved enabling environment.

We are aware that shifting development pathways is difficult without changing social rules and norms and behavioral patterns. Yet, we have made progress in identifying pertinent tools (based on Sida's Green Toolbox, but also USAID Climate Risk Management and SDC's Risk Reduction Integration Guidance) to build a relevant framework for assessing and addressing all pertinent aspects of climate change and environmental degradation, as well as a green transition as a process of socioeconomic transformation. The current technique will be further revised based on the findings and the knowledge obtained.

As part of the MSD approach, we have also been creating training modules that incorporate environmental and climatic change. There has not been much done in this area. Thus, the program and other partners and stakeholders, including Sida, will be guided in their knowledge of how to facilitate the green transition in institutionally sustainable, scalable, and inclusive ways.

The MSD approach provides the opportunity to comprehensively consider all six dimensions (geophysical, environmental, economic, sociocultural, technological, institutional, and political) and identify potential entry points for building a supportive policy environment, providing access to technology, innovations, and finance, stimulating the shifts in social norms and choices.

Related sources