Evidence will help policymakers understand what works, where, why and for whom. It can also tell them what doesn’t work, and they can avoid repeating the failures of others by learning from evaluations of unsuccessful programmes. Evidence also challenges what we might think is common sense.

In this blog post, we present the work of the PERFORM project in the Western Balkans and show how the project has been facilitating to improve key functions that contribute to evidence-informed policy making.

Pilot initiatives facilitated by PERFORM

PERFORM’s goal is to increase the relevance of social sciences in political and socio-economic reform processes. In early 2016, Serbia’s Public Policy Secretariat and PERFORM agreed to support four pilot initiatives linking groups of researchers with policy institutions in order to provide evidence for complex policy projects.

One of the participating policy institutions was the Ministry of Youth and Sports (MOS). What would staff in the MOS have done without the evidence provided by a group of social science researchers within the framework of PERFORM’s pilots? A senior official from the MOS stated, without much hesitation, that they would have sat together and talked about it to come up with some kind of conclusion.

Reviewing a supportive policy framework for young entrepreneurs is challenging. It involves registration of a business, access to finance, taxation, labour laws, etc. Sitting around a table to discuss such a complex array of policies, and come up with conclusions? You must be kidding! “Yes”, she said, “policy institutions in Serbia lack the analytical capacities to undertake systematic reviews on their own for gaining evidence for good quality public policies”.

How about drawing a research institution into the process? “Good idea”, she said, “but there are so many impediments: public procurement procedures of such services are too complicated, ministries make no provisions for research in their budget; and, the experience of working with researchers in the past has not been all that positive.”

This time, the experience of MOS was very positive. A group of researchers came up with some new aspects and developed them into details for the MOS analysts. Some of their ideas include:

- Easing access to venture capital for young entrepreneurs; linkages with “investment angels”. A new law on microfinance, tax exemptions for investments in start-ups, concept of tax loans for investments in research and development;

- Amendments to the Law on Foreign Currency Transfers to enable practical application of systems of electronic money transfers (such as PayPal);

- A more effective interface between research and enterprises to stimulate innovation;

- Introducing students to the concept of enterprises by providing the space in schools and universities for setting up companies which will be designed, implemented and operated by students.

What contributed to the success of the pilots?

When the project started the pilot, there was an interest but also a great deal of reservation. People from policy institutions referred to bad experiences from the past; policy recommendations provided by researchers were often not relevant to the policy issues on the table, and difficult, if not impossible to implement. Researchers were worried about their research results not being adopted by policy makers, and some brought the argument that conducting policy-relevant research would be a threat to academic freedom.

The initiative was guided by three objectives of:

- Improving the quality of public policies through relevant evidence from social science research;

- identifying the main factors that have impeded that collaboration so far; and

- developing a set of actions that will address the root causes.

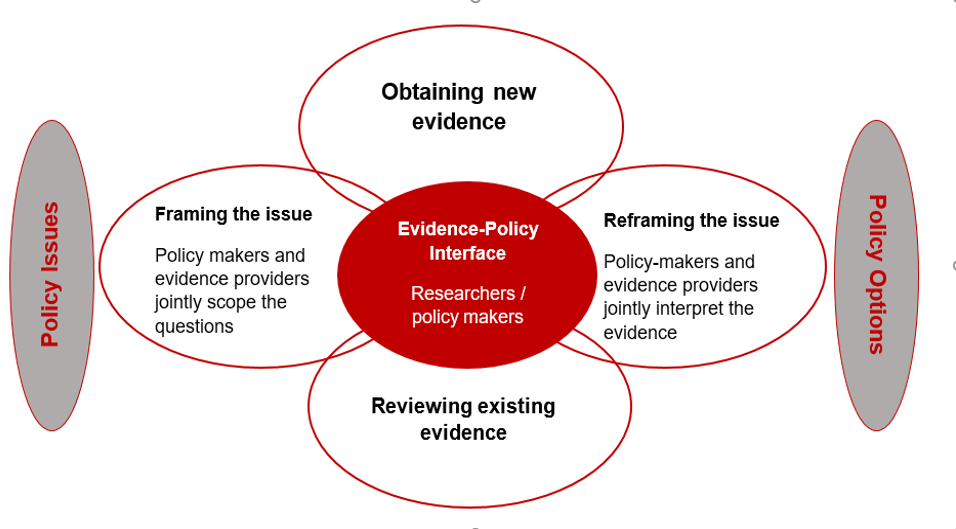

As shown in the diagram, analysts from participating policy institutions were supported in moderated workshops to frame the issues and problems and define policy questions at stake. The researchers then defined the research questions which provided the base for a “systematic review” of available experiences and knowledge, and the analysis conducted by researchers. These workshops were a key element for the success of the collaboration. Another important, quality-determining feature was the regular dialogue between the two groups during the process.

Reflection and learning

PERFORM facilitated a process of learning and reflection among the participating groups of stakeholders to identify those factors that constrict or prevent the process – ranging from public procurement of services to budget provisions, and capacities among researchers to conduct systematic reviews. PERFORM supported a separate study on the current regulations related to public procurement of services, and how that could be eased to facilitate procurement of research services.

The reflection and learning process helped to shift ownership of the improved system to stakeholders. At the end of the process, guidelines were developed for evidence-informed policy making, which will be incorporated into the new Law on Planning.

In the final evaluation, all participating partners highlighted the process of defining and framing the policy issues that they were expected to research as the most important step that ensured the quality of results. Researchers appreciated that their contributions were seriously and critically discussed, and taken up in policy documents. The exchanges and discussions contributed to building people’s analytical capacities and knowledge on evidence-informed policy making.

Evidence to guide decisions and policy making on controversial issues

Some policy fields tend to be strongly influenced by myths and traditions, particularly in conservative societies. Demography is one of these fields.

Here is a case in point: the population of most countries on the Western Balkans are shrinking. The impact on the society and its economy, particularly in rural areas, can be devastating. Political decision makers need to understand the complexity of the underlying reasons for these developments to be able to fine-tune an array of different policies. However, in conservative societies, politicians tend to take a rather crude pro-nationalist approach, which just does not work.

PERFORM has been supporting the collaboration between the Ministry that is in charge of population policies with a group of demographers. The input from researchers included training for staff of different ministries. They will work on drafting a new and evidence-based strategy for the government to reverse the population decline. The Ministry for Population Policy has now initiated the establishment of a commission with ministers from different portfolios to take effective measures in response to demographic developments. A small group of researchers has been appointed to provide advice and evidence to guide the Commission and its members in developing effective public policies for their field.

The fact that a commission chaired by the Prime Minister takes in scientific advice is an opportunity to demonstrate the value of evidence in policy making, particularly when political decision makers deal with controversial issues, where myth tends to weigh heavily over facts. This work of the commission is just beginning.

PERFORM has to find points of leverage, where it can trigger significant change with limited resources. Demography is a risky policy field to enter; decision makers may reject evidence in favour of myths and traditions. However, since the process includes several top level political decision-makers, PERFORM concluded that this will provide an opportunity to demonstrate the value of evidence.

Continuing from here – facilitating broader systemic change

How can project initiatives move from a small number of successful pilots to a broader systemic change? A consistent use of good quality evidence in public policy and decision making will be a game changer. The practice will reduce bias, arbitrariness and incompetence from the process and will significantly enhance their effectiveness to stimulate economic development and social reform processes.

The partnership with the Public Policy Secretariat and the subsequent pilots was a suitable entry point for PERFORM. The pilots allowed the project to gain a much better insight into the system, in particular, the political economy and other underlying factors that are responsible for social science research and policy institutions not working together. The pilots also provided opportunities for learning loops with all participating stakeholders, which allowed them to identify underlying reasons that cause underperformance in the system. The project was able to build up linkages with those who have the will and the skill but also the power for change.

The main takeaways from this blog post are:

- Lasting systemic change (sustainable impacts at scale) requires shifts in attitude and behaviour among stakeholders to adopt and follow new practices;

- Changes in attitudes and behaviour need practical and positive experiences in collaboration, accompanied by learning loops and reflections. Collaborations between policy institutions and research groups will need to be accompanied by events and strategic communication; this will initiate and contribute to a broader public and political debate on the practice.

- For changes in attitudes and behaviour to take broad effect, mechanisms and structures in the system are required that ease and facilitate the drawing of evidence into policy making. These include e.g. guidelines and legislation. Embedding such rules into legislation is a significant task and will require strong and strategic partnerships.

Additional resources

Authors

Martin Dietz heads the PERFORM project. He has worked in development cooperation for over 20 years. Following his PhD from Reading University and a lectureship at King’s College London, he started to work as a consultant for a couple of years. Later he took over the management of a consulting firm. During that period, he worked on a wide range of assignments in numerous countries, focusing on South and South East Asia as a region. During recent years he worked mainly on development projects that take a systemic approach, and he gathered experience in a range of different sectors with that approach. He enjoys, and he has a long experience in interacting with people to understand and appreciate complexity in systems, how people relate to each other in such systems and how changes can be induced.