This year’s rice planting season in Laos started with droughts, making it difficult for farmers in parts of the country to plant after a heat wave in April and May. Then, just before harvesting season, Typhoon Yagi swept across Southeast Asia, bringing severe flooding to Laos. With climate change progressing quickly, Lao farmers must brace themselves for an increase in the frequency and/or severity of droughts, fires, storms and floods. These events are causing more and more damage to crops, homes, infrastructure and the economy. Helvetas has therefore been supporting Laos in developing a productive, inclusive and sustainable agricultural sector, and recently undertook a study looking back at two decades of support.

Over the last 20 years the face of agriculture in Laos’ has changed significantly, marked by a gradual shift from mostly subsistence agriculture to commercial agriculture. The predominant farming systems in the past were focused on home consumption, with rice as the main crop. Over time, additional crops have been introduced to farmers. The main drivers for change towards more commercial crops are increased market accessibility in rural areas and the demand by neighboring countries for natural resources. For the latter, investments have been made in large rubber plantations and entire landscapes have been cleared to satisfy the demand of animal feed industries. Maize and cassava, which were introduced by mainly foreign companies, as well as coffee, rubber and tea, are commercial crops that have changed farming practices.

While this has led to economic gains for farmers, cash crops are often grown as monoculture and utilize unsafe and unsustainable practices (see the research paper “The Toxic Landscape”). Additionally, the reduction in poverty has been uneven, with small farmers and members of ethnic minorities living in remote areas continuing to be at a higher risk of poverty; an estimated 200,000 households in rural areas still live in poverty. These households face hardship, not least as a result of extreme weather and high inflation rates.

Evolution of agricultural extension support

Eighty percent of Laos’ eight million inhabitants rely on agriculture as a livelihood source. Recognizing the importance of agriculture in the country’s development, the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, with Helvetas as its implementing partner, has been supporting Laos in making agricultural systems more effective, inclusive and sustainable for over 20 years. This includes developing rural advisory services (also known as an agricultural extension system) together with the government of Laos.

Agricultural extension and advisory services support farmers and rural producers through training, information, and brokering linkages to markets and services. The public extension services are provided by staff of District and Provincial Agriculture and Forestry Offices (DAFOs and PAFOs) that operate under the guidance of the Department of Agriculture Extension and Cooperatives (DAEC). DAEC is responsible for capacity building, including provision of training on extension methodology, promotion of agro-processing and monitoring the work of farmer organizations.

The initial focus within the Laos Extension for Agriculture Project (LEAP) from 2001 to 2014 lay on the idea of “Extension for Everyone” and thus covered the whole country, focusing on capacity building of the public extension services. Realizing that by targeting everyone, the ones who most need it may be left behind, the follow-up Lao Upland Rural Advisory Services (LURAS) project, which runs from 2015 to 2025, has a more restrictive focus on poverty-affected upland provinces. Reflecting the urgency of climate change, in the current and last phase LURAS put sustainability and climate change adaptation at the center of its efforts with the Green Extension Approach.

Green extension in practice: Insights from Nam Ka Village

Nam Ka village illustrates what Green Extension can look like in practice in Laos. Nam Ka is located in the uplands of the northern province of Xieng Khouangone and is one of the 43 villages where LURAS partners are applying the Climate Resilience Extension Development (CRED) approach. The village is mainly populated by Hmong, a minority ethnic group in Laos that relies mostly on agriculture, especially chilis and cattle, for their livelihood. They have been struggling with frequent disasters such as flooding that wash away irrigation channels during the rainy season, as well as a vicious fungus attacking their chili plants. Cattle rearing also has its own set of challenges: To increase their earnings, they traditionally “slash and burn” nearby forest areas to plant grass for cattle, contributing to deforestation as well as degrading air quality. Their cattle, too, were affected by diseases – further impacting their earnings.

Following the community-based CRED methodology, Helvetas developed a Green Extension toolbox that guided a process for helping the village seek solutions for these problems. The process starts with community meetings to identify key challenges and to select the adoptive measures that can address them. Such interventions aim to address all three pillars of sustainability – social, environmental and economic – in an integrated manner.

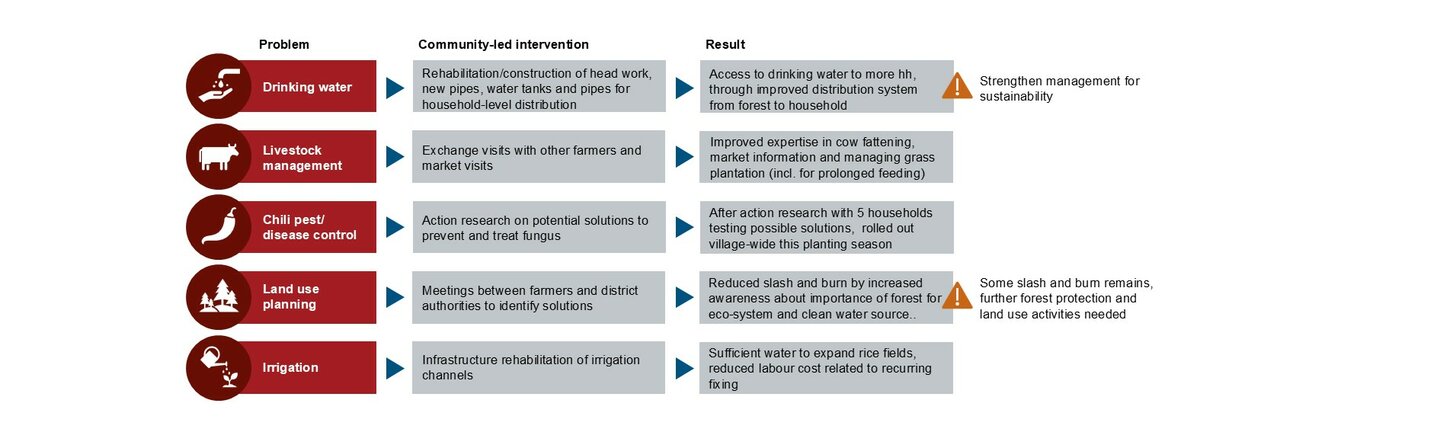

In Nam Ka, the community decided to focus on five areas: (1) drinking water improvement; (2) livestock improvement; (3) chili pest and disease control/prevention; (4) land use planning; and (5) irrigation improvement. As illustrated in the graphic below, the community came up with a plan, including how they could address these issues themselves to become more resilient, leaving the project to provide minimal external technical and financial support for some materials.

Learnings from two decades of engagement

After two decades of supporting agricultural extension in Laos, Helvetas took stock of the changes in the extension services and captured learnings that could be shared with the wider development sector in Laos and globally. To assess change, the study, which was conducted by Helvetas alongside a Lao consultant, evaluated the current status of the Laos extension system according to three main features of Kägi and Schmidt’s model of an effective pluralistic agricultural extension system: delivery capacity, effective demand, and conducive policies. Below, we delve deeper into the insights from each of these areas.

Delivery capacity: Centering pluralism and adaptation

Delivery capacity refers to the capacity of the providers of agricultural extension (e.g., farmers to farmers, farmer groups, companies) to deliver their services effectively. Within this area, the project team learned that:

- Consistent, long-term partnerships make all the difference. The Department for Agricultural Extension and Cooperatives (DAEC) was set up when LEAP started. Ever since, there has been a very constructive relationship between the projects and government partners, which has been enabled by consistency in the interlocutors and their continuous interest in pursuing results-driven activities. Additionally, LURAS has provided platforms for the government to gain exposure and visibility for Laos’ experiences as well as its challenges regionally and even at international meetings (e.g., for instance by co-founding the Mekong Extension Learning Alliance (MELA).

- Extension works. The focus of extension services has shifted from providing technical agricultural expertise (such as input supply or agricultural practices) to a broader menu of services, like facilitating market access and enforcing regulations. This shift highlights the significant growth in technical capacities achieved through initiatives such as training programs for public extensionists, demonstration learning centers, peer learning opportunities and action research.

- Pluralism is needed. Starting with an exclusively public extension system in the early 2000s, private extension providers increasingly emerged due to the increase in commercial crops and competition. LEAP and LURAS accelerated this shift towards a more pluralistic system. Through this, the (public) agricultural extension staff became part of and contributed to a diverse network of extension actors in Laos; this landscape ranged from local to global levels and included actors from the public and private sectors as well as civil society organizations. Each actor has its own set of constraints and risks, such as the continued reliance on donor funding, a lack of sufficient effective manpower in the public system, and vested interests by commercial actors in the private sector. While a pluralistic system can’t eliminate these issues, it helps to balance them.

- Responsible engagement with agribusiness is an important part of sustainable agriculture. LURAS is helping farmers learn new ways of organizing themselves, adding value to their products, and partnering with the private sector in forest-friendly value chains like coffee and tea. More than 4,000 farmers (more women than men) have increased their income. In particular, coffee farmers have doubled their income by improving their yields and by moving up in the value chain, expanding from selling cherries to high quality beans.

- Inclusion requires representation. The early extension efforts under LEAP sought to provide “Extension for Everyone.” However, with a limited number of women among the technical staff or staff that spoke the language of various ethnic groups, the public extension system was failing to be inclusive. The shift to a specific focus on poverty-affected upland provinces under LURAS was an effort to address this. But even though LURAS promoted a more prominent role for women in technical jobs, most of them are still assigned administrative positions within the extension system, leading to no significant change to date.

Effective demand: Organizing for influence

Enhanced delivery capacity can only have a positive impact if it meets demands. Effective demand therefore refers to the capacity of farmers to make their voice heard so that extension services respond to a genuine demand. In this regard, the LURAS team found that:

- Organized Farmers are stronger. Lao farmers’ voices are now better represented thanks to the successful Lao Farmer Association (LFA) created in 2014 and registered as an association in 2023. As of 2024, LFA represents 190 farmer groups and is well organized with a functioning secretariat and the necessary governance mechanisms in place. This has earned it a respected place among the government, development partners and sector stakeholders. In 2023, the LFA joined more than 100 policy meetings. According to the capitalization study, the growth and success of LFA can be directly attributed to LEAP and LURAS support. Additionally, the DAEC plays an important role providing advice and guidance as well as implementing joint activities with LFA.

- Ways of engagement with farmers matter. The strategy for implementing LURAS field activities is known as Green Extension. This is a type of rural advisory service that supports the scaling up of sustainable agriculture by facilitating socio-ecological learning among farmers. Socio-ecological learning combined two key concepts: “Social learning” means that rural people are actively involved in the generation and sharing of knowledge, “ecological learning” means that innovations are tested under local conditions and take into account interactions between different activities within the farming system. The essence of this is captured within one of our main tools: the CRED approach, which was previously illustrated with an example from Nam Ka village. Following CRED, communities identify key issues, create action plans, contribute labor and materials, and monitor their own initiatives. The project provides only minimal financial and technical support thus encouraging community ownership and sustainability. By centering the community, tailored solutions based on good practices naturally emerge over generic blueprints. While this has proven to be critical to effectively promote climate change resilience, it also renders scaling more challenging.

- Technocratic solutions are meaningless without solidarity. The CRED approach further demonstrated that social solidarity and the need for cooperation with various government offices may be the most important factor in improving climate resilience. Without it, it is impossible to identify shared interests that enable collective action. To facilitate this, focusing on intrinsic communities (e.g., according to geographic or ethnic clusters) rather than administrative villages was shown to be helpful.

Conducive policies: Bridging the gap between theory and practice

Finally, for an effective extension system, enabling policies need to be in place and extensionists need to be able to contribute to policy-making processes, amplify the voice of farmers and put existing policies into action. In this regard, the study shed light on the following:

- Leveraging government structures facilitates change. In Laos, government-led sector and sub-sector working groups address major thematic areas of development. LEAP/LURAS as the secretariat of the Sub-Sector Working Group on Farmers and Agribusiness, co-chaired by the DAEC and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, has effectively leveraged this 17-year-old platform to initiate and promote policy changes. As an example, the “Green Extension” approach was included in the Green Growth Strategy of the government and anchored in the “Green and Sustainable Agriculture Framework for Lao PDR to 2030.” While government buy-in is always critical for sustainability, this is even more true in Laos considering its communist government. The members of the Working Group expressing their appreciation for bringing relevant and timely topics to the table is thus a testament to a long-standing trusted and relevant partnership.

- Knowledge platforms are effective. The knowledge-sharing discussion group (with 4,500 members) and online document repositories LaoFAB (English) and Lao44 (in Lao) were reported to be among the most important tools for policy makers. Key reasons include: (1) LaoFAB’s repository is seen as an indispensable resource for accessing critical documents and reports, which are often difficult to find elsewhere; (2) LaoFAB fills a critical gap by providing a space for development professionals to share knowledge, experiences, and ideas; (3) LaoFAB is valued not only by local users, but also by international researchers, NGOs and development practitioners working in Laos. The moderator of the LaoFAB google group and repositories prepares weekly updates with the most important news in the sector, shares stories from farmers (collected by LFA), and has a blog about climate change in Laos, as well as a monthly weather bulletin.

- Evidence-based policymaking is welcome. Under LEAP and LURAS numerous pieces of research and publications were conducted that served to set the agenda of policy dialogue (e.g., “The Toxic Landscape”). Other reports completed during last two years include a “Meta-study of climate adaptation measures tested by upland farmers in Laos" and “Changing Perspectives: Understanding Chinese Agricultural Investors in Northern Laos.”

- Gaps between policies and implementation remain. Despite many well-formulated policies, a discrepancy between policies at the national level and their implementation on the ground is evident. This may partially be attributed to different understanding of policy and policy implications at various levels, as well between locations. LURAS plays an active role in building awareness and capacities for policy implementation through Responsible Agriculture Investment (RAI). RAI is a set of principles for agribusinesses to align their practices, procedures and operations with principles of responsible investment in agriculture. LURAS has been researching the relationship of foreign investors (mainly Chinese) with local Lao communities, with the aim to learn about the local practices and to support awareness about RAI.

Beyond these specific learnings, the complementary LEAP and LURAS projects demonstrated what a difference long-term commitment can make. The support spanning 24 years without gaps between projects and phases was unanimously praised by all contacted stakeholders. It reflected the mutual commitment from the government of Laos, Helvetas and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation.

The government had an open mind to learning through trial and error, engaging with different stakeholders, and proactive collaboration with technical officers and directors at DAEC and PAFOs in the provinces. DAEC has been a role model in knowledge sharing, collective learning, facilitating processes and engaging with other sectors. This laid the ground for the current pluralistic extension system in Laos, which uses the Green Extension approach tailored to local contexts as the most effective way for farmers to maintain the natural resource base and adapt to climate change effects.

About the Authors

Lara Ehrenzeller is the Regional Business Development and Communications Officer for Helvetas Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar.

Marieke van Schie is the LURAS project manager for Helvetas Laos.

Souvanthong Namvong is the Deputy Director for the Department of Agriculture and Extension (DAEC) at the Laos-PDR Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry.

Helvetas’ Work in Laos

Since 2001, Helvetas’ country program in Laos has been dedicated to improving people’s livelihoods. Today, approximately 70 staff collaborate with civil society organizations, local businesses and academia to advocate for public institutions to realize people’s basic rights and create opportunities for decent employment and entrepreneurship. The economic, social and political empowerment of disadvantaged groups – especially women, youth and marginalized ethnic groups – is at the center of our efforts.

To achieve these objectives, Helvetas invests in technical expertise, including by promoting green agricultural advisory services, strengthening dam safety capacities, and establishing work-based learning programs for youth. However, for skills and technical expertise to translate into change, an enabling environment is needed. Helvetas works to influence policy in our working areas and supports government institutions in increasing their engagement with and accountability toward their citizens. While the space for civic action is shrinking, strengthening local civil society organizations to be the voice of communities is a cornerstone of our efforts to attain basic rights. Finally, we promote an enabling environment for businesses operating in the unique context of one of the few communist countries in the world. Helvetas thereby focuses on developing value chains and accessing international markets in the tea and coffee sectors, as well as on products that can be sourced responsibly from the forest, such as cardamom and red mushrooms.